FACE BLINDNESS IN A NUTSHELL: PUTTING A HUMAN FACE ON PROSOPAGNOSIA

By: Austin Lim

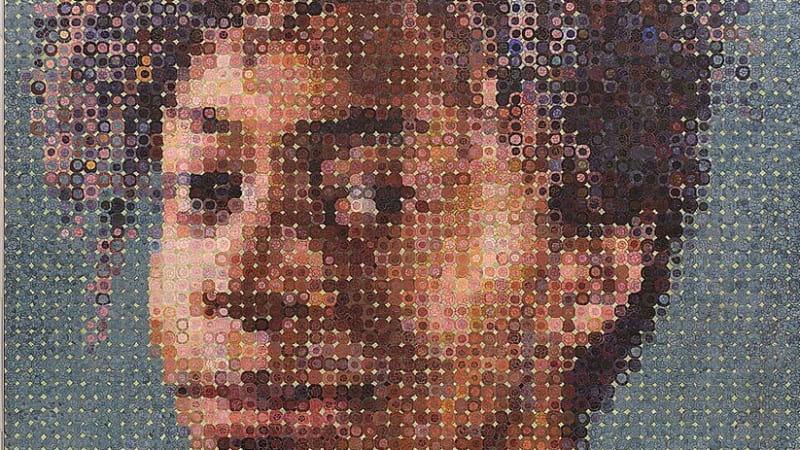

Chuck Close mosaic of a woman’s face in the 86th street subway of New York

Contemporary painter and photographer Chuck Close has displayed artwork at famed galleries around the world. He has published several books of his paintings and was an acting member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities. Some of his works have even been sold for millions of dollars on auction at Sotheby’s. The cover art of Paul Simon’s 2016 album, Stranger to Stranger? Another Chuck Close masterpiece.

Contemporary painter and photographer Chuck Close has displayed artwork at famed galleries around the world. He has published several books of his paintings and was an acting member of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities. Some of his works have even been sold for millions of dollars on auction at Sotheby’s. The cover art of Paul Simon’s 2016 album, Stranger to Stranger? Another Chuck Close masterpiece.

Whereas some artists prefer to paint landscapes or still lifes, Close has a fixation with faces. Between his multicolored mosaics of faces and his massive, nine-foot-tall photorealistic acrylic painting of his own cigarette-smoking visage, it is apparent that the human face captivates the artist.

Close’s passion for painting faces is rather ironic, considering his unique neurological condition – he was born with prosopagnosia, or “face blindness.” He is unable to recognize a person by looking at their face. And he is not alone. One in fifty Americans have some degree of face blindness.

What exactly does face blindness mean? Imagine looking directly at someone. Your gaze takes in eyes, a nose, a mouth. You’d recognize that you were looking at a face. But if you had prosopagnosia, you wouldn’t be able to match that specific face with any other face you had seen before. As a result, you couldn’t identify the person. You might not be able to recognize your spouse or children, despite seeing them on a daily basis over the span of years. If the person with whom you areconversing turns their head just a few degrees, you might think you were looking at a different person; one you have never seen before. In severe cases, you wouldn’t even recognize your own reflection.

People with face blindness don’t have abnormal visual acuity. Their visual perception is not particularly worse or better than average, and they can see just as well as a similar neurotypical person. They can differentiate shades of colors, identify visual patterns, and see in 3D. They can distinguish objects from others like it, and they can find their car in a parking lot.

Prosopagnosia doesn’t equate to a deficit in memory of people, either. There is often no associated deficit in overall intelligence. A person with prosopagnosia would have the same ability to remember discrete facts and learn physical tasks just as well as any other person. They can remember names and specific details about a person after conversing with them.

It’s not their inability to see or learn or remember that’s problematic. Rather, the difficulty lies in the specific recognition of faces.

The brain processes and identifies faces using different neural connections than those used for identifying objects. It is possible that this specialization is a consequence of our early evolutionary ancestors’ budding social lives. Their interactions consisted of communicating with several other early hominids who might have had the same body shape, stature, and posture. Because bodies may look alike, minute differences in facial features may have been the key to distinguishing a friend from an enemy. Having such a highly specialized face-processing pathway in the brain ensures that these tiny differences were noticed, thus permitting social interactions that were necessary for survival of the species – recognizing the face of a foe would trigger a cautious or aggressive response, whereas recognizing one’s offspring would activate defensive or protective behaviors.

Some people are born with prosopagnosia. Others may develop face blindness following brain damage (such as a stroke). But what exactly changes in the brain that results in prosopagnosia? The prevailing theory involves a deficit in a region of the brain called the fusiform face area. This structure is tucked deeply in the temporal lobe at the base of the brain and is highly specialized for facial recognition. It incorporates the individual features to create a unified image. That composite is what we use to identify faces, and then other parts of our brain match the face with an identity. But for people with prosopagnosia, the fusiform gyrus is unable to perform this integrative function, resulting in the inability to identify faces.

To manage this neurological disorder, people with prosopagnosia often develop mental shortcuts and use social cues to improve their ability to recognize others. First and foremost, they may search for highly unique facial features such as birthmarks or scars to quickly identify individuals. For most patients, recognition of these distinctive and uncommon features seems to be independent of fusiform gyrus processing. They may also look for non-facial characteristics that give a clue to a person’s identity: body shape, mannerisms, gait, hairstyle, or clothing. Appearances aside, other senses can be used–hearing someone’s voice or catching a whiff of a particular perfume or deodorant may be sufficient clues to figure out who they are interacting with. As a last resort, they may stall during a conversation by asking intentionally vague questions such as “How’s your family?” or “Where were you coming from?” in order to establish some sense of context or uncover relational clues and other information that will help identify the person.

Prosopagnosia might seem like a rare neurological disorder, but at 2% of the US population, it is more prevalent than you might think. If you are among these people with prosopagnosia, you may be surprised to hear who else shares your struggle–or at least has some degree of face blindness. Actor Brad Pitt has been accused of being a snob when he passes a coworker on set and doesn’t recognize them, despite having had multiple conversations with them. Anthropologist Jane Goodall takes the opposite approach: in her autobiography, she writes that instead of facing the potential embarrassment of ignoring a colleague, she copes with her prosopagnosia by “pretending to recognize everyone.” In an interview about the 2015 movie Steve Jobs, former Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak had very little to say about whether or not the actor selected to portray Jobs actually looked like him, commenting “to me faces don’t matter that much anyway.”