THE DEVIL IN ALL OF US: MOB MENTALITY

By: Sarah Moore

No one’s about to claim that the Holocaust was a good idea. Or that gang rapes are advisable. Or even that bar fights are predicated on anything but group idiocy. Trampling people in evacuations and running them over in Wal-Mart sprees just isn’t cool, no matter what. Yet this stuff happens more often than it should.

I started thinking about this the other day when I read that Jerry Sandusky had finally been convicted on roughly eight million counts of child abuse and related crimes. If necessary, his adopted son was even willing to take the stand.

My initial thoughts are probably not suitable for publication, but after I calmed down a bit, I realized that what disturbed me most – and I think a large percentage of Americans will agree with me when I say this – is not that it happened in the first place, but that so many people found “reasons” to ignore what was going on.

And isn’t that always what disturbs us most? Sure, we’re upset when a woman gets raped, but we’re really upset when we find out twenty people stood by and did nothing about it. What is it about being in a group that makes some people say, “At this moment, this seems fine”?

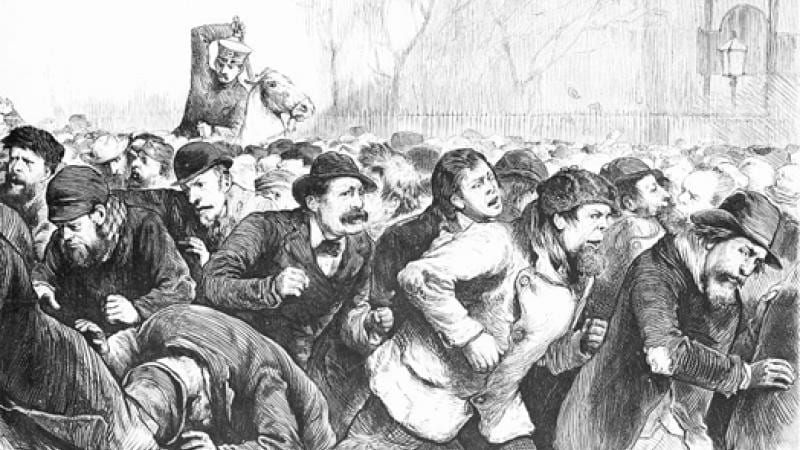

We most commonly associate mob mentality, or herd mentality as it is sometimes called, with violence and assault. But for some reason I really didn’t think that could be the whole story; after all, behaviors that pervade entire species are rarely maladaptive.

So I did some research, and found that herd mentality is hardwired into all of us. One study, conducted by Professor Jens Krause at the University of Leeds, found that it only takes 5 percent of a crowd to influence the other 95 percent in a specific direction. More specifically, researchers asked 200 people to mill around in a hall, then gave 10 of them directions on where to walk. The rest eventually fell into line.

In a crisis situation, this makes sense: we want to follow the guys and gals who seem to know what’s up. Herd behavior can aid in bonding, and it can clarify social expectations, so it has a pretty clear adaptive function. But it can also lead us astray, especially when emotion is running high. Then people who normally wouldn’t condone bad behavior find themselves engaging in it, even though later the predominant emotions are shame or confusion.

Strictly speaking, the Sandusky affair may not fit the definition of mob mentality because the travesties happened in drips and trickles rather than all at once. Nevertheless, the defining characteristic of the term is a loss of individualism and a sense that “everyone is doing it.” When it came to the leaders involved in the case – football coach Joe Paterno and university President Graham Spanier, both ousted, as well as Vice President Gary Schultz and Athletic Director Tim Curley, both awaiting trial – these characteristics definitely apply.

The lesson here? Some people are definitely more amoral and bigger jerks than others … but we all need to be careful.